Referee Training Course Manual - Section 3

Referee Training Course Manual

Section 3: Notes to be Given to Course Attendees

This Section provides (or references) a set of papers that should be given to all course attendees. The details of the papers and when they should be passed to the attendees are listed below:

3.1 |

Laws course preparatory questions (not available in this online course). A set of 41 questions (without answers) for course attendees to prepare answers before the course. They have been designed to help the attendees to find their way around the Laws book. Available to Examining Referees on request to the Laws Committee Chair. |

3.2 |

Laws course preparatory questions with answers (not available in this online course). As 3.1 but with a set of answers for the course leader. Available to Examining Referees on request to the Laws Committee Chair. |

3.3 |

The Tournament Regulations for Refereeing (available online and in the Laws). The current Tournament Regulations for Refereeing, version 1.5 of which are printed at the back of the Laws Book. |

3.4 |

Guidance to Refereeing on the Lawn A detailed set of advisory notes on refereeing on the lawn, which should be given to all examination candidates before the first practical session on the lawns. |

3.5 |

A set of wiring diagrams to be given to attendees when Law 16 is about to be discussed |

3.6 |

Appendix 3.4: Guidance to Refereeing on the Lawn

As a referee on call, you should first establish the state of the game - but only insofar as it is relevant to the matter in hand [Reg R3.2]. The important principle implicit in this caveat will be discussed as part of the 'Laws' section of the course.

A. Watching Questionable Strokes

1. Marking the Position of the Balls

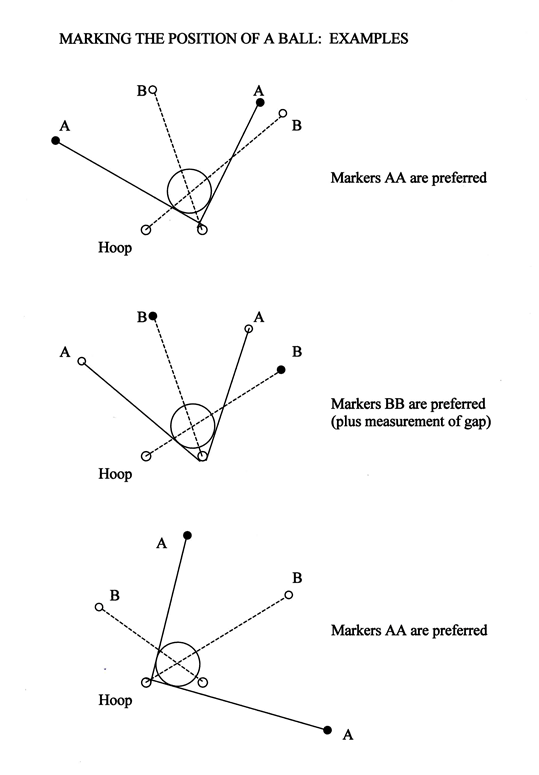

The purpose of marking the position of the balls is to ensure that they may be accurately replaced, should a fault be committed; but this must be done in a way that does not interfere with or assist the striker. The method used is essentially one of taking bearings on fixed points and recording them (by means of markers). There are two guiding principles which should be observed when precision is important:

- The position of a ball is best defined by bearings which intersect at right angles;

- A bearing is better defined by the edges of ball/wire/peg than by their centres, and mixing the two (centre of ball, edge of wire) can lead to mistakes in replacement.

These two guiding principles may conflict, particularly when a ball is close to a hoop (a check measurement of the gap can be useful in such positions). The first should in practice generally take precedence - it is usually better to mark in a way that favours a good intersection of the bearing lines than one which accurately defines lines with a poor intersection.

The standard of accuracy required in marking depends on how critical the position of the ball happens to be: for example, the precise position of a target ball in a hampered shot is rarely vital and can safely be recorded by a single marker to one side of it. It is bad practice to delay the striker by indulging in unnecessarily precise marking.

Small markers are more accurate than large ones: golf-ball markers are usually used (and a cork can be as convenient way to store them). Coins should not be used, because of the risk of expensive damage to mower blades if left behind on the court.

2. Assessing the Likely Outcome of the Stroke

It is important to form some view in advance, of the likely outcome of the striker's intended stroke - if it is successful - and the faults most likely to be committed (you may find it useful therefore to ask how the stroke will be played). This helps to prepare mentally for what to expect, in terms of sounds (mallet striking ball or hoop, ball hitting hoop, peg or other balls) and of the path of the striker's ball and others likely to be affected by the stroke. It also helps you decide where best to take up position to watch the stroke.

Differences between expectation and actuality may help in judging whether an irregularity has occurred. But it is important not to pre-judge the outcome of the stroke: the seemingly impossible does happen, and the unexpected is not necessarily the result of a fault.

3. Positioning for Best Observation

This follows naturally from stage 2 and will rarely give problems. You may find it necessary to position yourself in a way the striker does not like - for example, close to the line of the shot - but do not be deterred: you have the power to decide where to watch a stroke from [Reg R3.5.2]. You should however ensure that you do not obstruct the shot, that you will not be hit by the striker's mallet and that you will not interfere with the likely movement of the balls during the stroke. Wherever possible, ensure that your shadow does not fall across the striker's line of play.

In some situations, two referees may be needed to ensure that everything can be properly observed. If you think that that is necessary, do not hesitate to call another referee to assist you.

4. Giving Your Decision

Three simple points to bear in mind:

- Be decisive

You will not always give a decision with which the striker agrees. In many situations, the verdict depends to some extent on individual judgement and the standard you set may not accord with the standard expected by the striker (though it should be tolerably close to other referees' standards); and you may simply get it wrong. But you must decide whether or not a fault has been committed - it is not a matter for you to debate with the striker. Hesitation in delivering your verdict may invite dissent and certainly weakens the striker's confidence in your competence.

Remember, though, that the striker may be more aware than you that a particular fault has been committed (perhaps you were unsighted - the fault may not have been the one you expected and so positioned yourself for) and must draw your attention to a fault he believes he has committed, even if you thought the stroke was clean: your presence does not relieve the striker of his obligation, as joint referee of the game, to 'immediately announce any error he believes or suspects he may have committed' [Law 55.2.1]. But the decision is still yours.

- Be clear

Give your decision in terms that cannot create doubt: 'yes' could mean almost anything, 'fair' can all too easily be misheard as 'fault'. The use of the terms 'clean/fault' (or 'hit/miss', if appropriate to the situation) helps to minimise the scope for confusion.

- Be prompt

The least important of the three - it is better to be correct than to be quick - but it is dangerous to consider your decision for too long: your memory of the stroke will fade quickly, the circumstances (a tricky Rover hoop that will win the game if it is clean and lose it if it is not) will flash back into your mind. But don't rush unnecessarily: some strokes may have outcomes which thoroughly surprise you and you may need a moment to think through what must have happened. All the same, the quicker you can make up your mind, the easier your decision is likely to be.

Whether or not to volunteer explanations is a moot point. I incline to the view that it is better not to do so (unless asked, of course [Reg R3.6], unless it is obvious that the striker simply does not appreciate what might have gone wrong and so should be told, so that he does not through ignorance commit similar faults in future (this is most frequently a problem with high bisquers - particularly with crushes - and with hammer shots, where standards can differ markedly). But it is really a matter for personal taste.

B. Judging the Positions of the Balls

One general point - obvious, but worth stating nonetheless - is of overriding importance in judging the position of a ball: it must not be touched or moved unless to confirm a decision you have already made. Similarly, no equipment in a critical position - hoop, peg or boundary cord - should be touched.

1. Ball Through a Hoop

The best test is by eye, at the level of the centre of the ball (i.e. about two inches above ground level). Hoops are frequently not upright, or are twisted; this makes judging from any other position unreliable.

It should not be necessary to confirm your opinion with a physical test, though the striker will normally expect you to do so if the decision is unfavourable and it is therefore wise to check in such circumstances. Check with a straight edge - held horizontally - from below the ball, working up to it and placing as little pressure as possible on the hoop (both precautions help to reduce the possibility of disturbing the hoop). Ensure that the straight edge really is straight: rulebooks and banknotes often are not. A thread of cotton serves well.

2. Ball Off the Lawn

An unaided ocular test is often less satisfactory in this case, both because defining the true line is much more easily done with a straight edge of some kind and because it is not easy to judge a vertical - from above the line - simply by eye. A square or rectangular-headed mallet is the most useful tool for the job: again, do not rely on the "rulebook method" (if its pages have not been cut at right angles to the spine or the ground is not level, it will be thoroughly misleading). In defining a chalk line, you should try to judge the path followed by the wheel that marked it.

3. Ball to be Placed on the Yard Line

You may occasionally be called upon to replace a ball in the yard line area accurately on the yard line, usually when a cannon is a possibility. Near a ball on the corner spot, simple measurement (with a mallet) is often all that is necessary and you are simply acting as an independent adjudicator. But it is sometimes necessary to judge replacements well away from corners, where a cannon may arise and where the problem is one of determining a true right angle rather than measuring the yard itself.

The relative position of the critical balls - the ball on the yard line and the ball in the yard line area - can only be determined accurately from a distance and, in the absence of a reliable tape measure, which enables you notionally to 'translate' the position of the ball in hand well out into the court, the task can often be carried out by measuring from reference points such as corner hoops which can be assumed to be equidistant from the boundaries. But there are times when you will unavoidably be forced to improvise.

4. Wiring Lifts

4.1 Confirming Entitlement

If you are called to adjudicate a wiring lift, you must first confirm that the claimant has not yet played the first stroke of his turn and that the adversary is responsible for the position of the ball for which a lift is being claimed [Reg R3.7].

4.2 Visualisation

The key to successful tests for wiring lifts is first to visualise the stroke by which the claimant's ball will attempt to strike the least accessible part of the target(s) available to it - with (in the case of a potentially hampered shot) the least advantageous part of the mallet face. What, precisely, is the obstacle? Which side of the target is hardest to hit? Which is the least accessible part of the mallet face? What path will the mallet take in making the stroke?

4.3 Testing

The method used for testing is to place trial balls at key points along the path the claimant's ball must follow to make the stroke you have just visualised: in contact with any obstacles along that path and (if necessary) against the target itself - taking care, of course, not to move it.

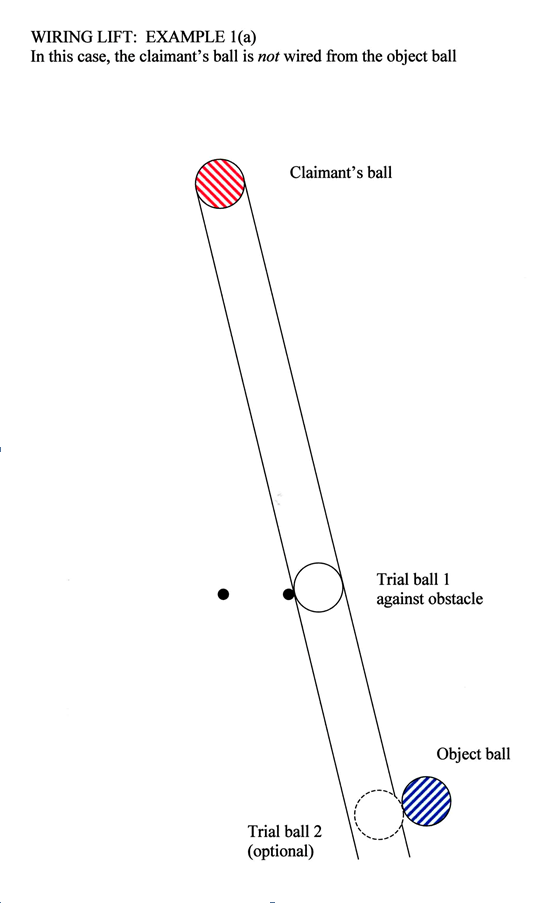

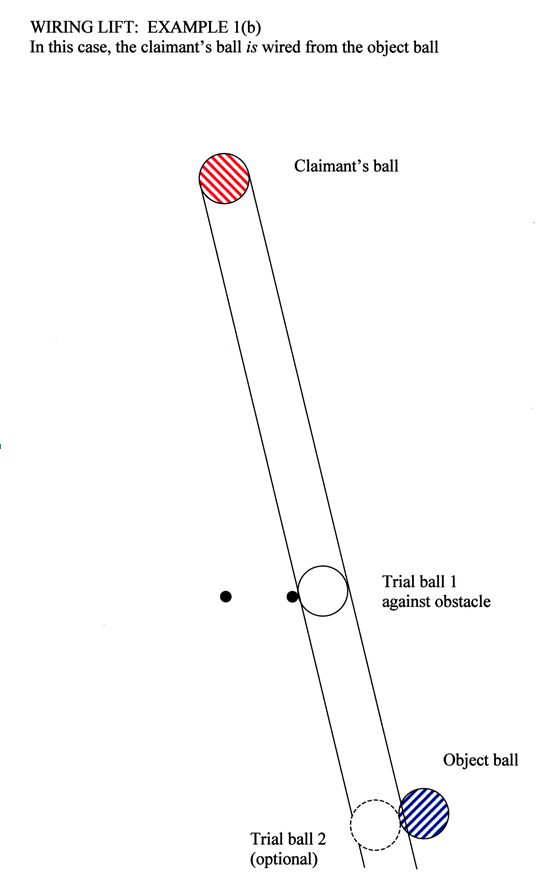

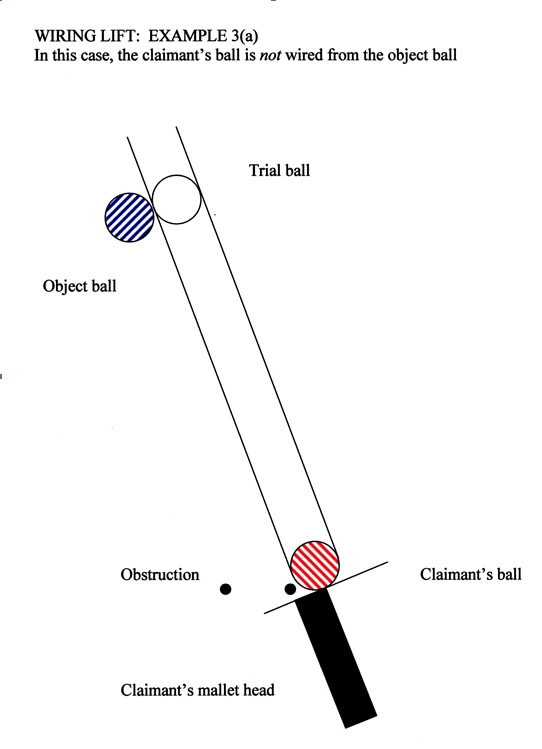

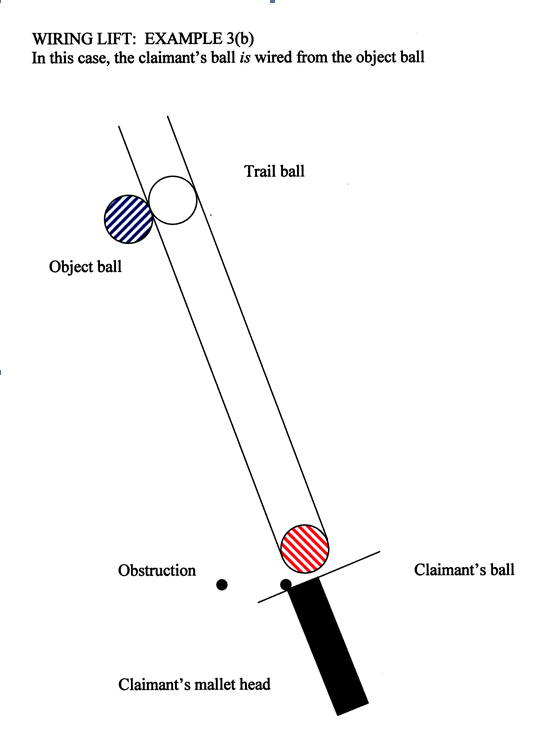

- Obstructed path to target [Law 16.3]

In principle, this is the most straightforward test. Trial ball(s) must be placed against the obstacle(s) - if necessary, held in place by wedges or coins - and next to the target ball along the line of the shot. Diagram 1 illustrates the most common case: (a) is not wired, (b) is.

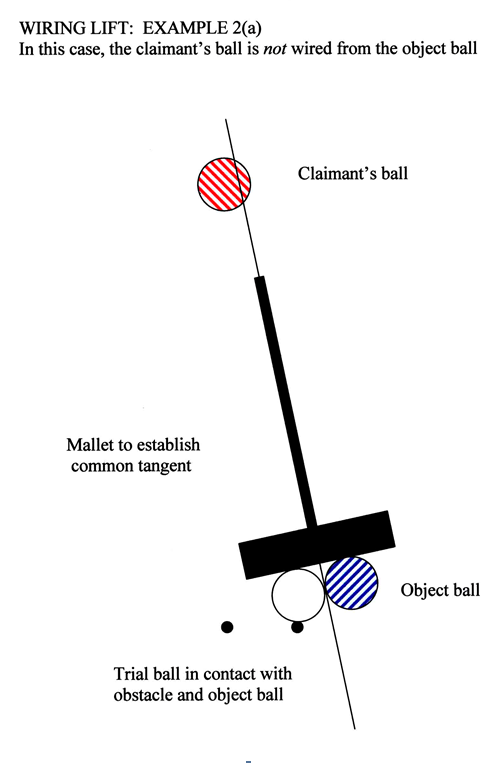

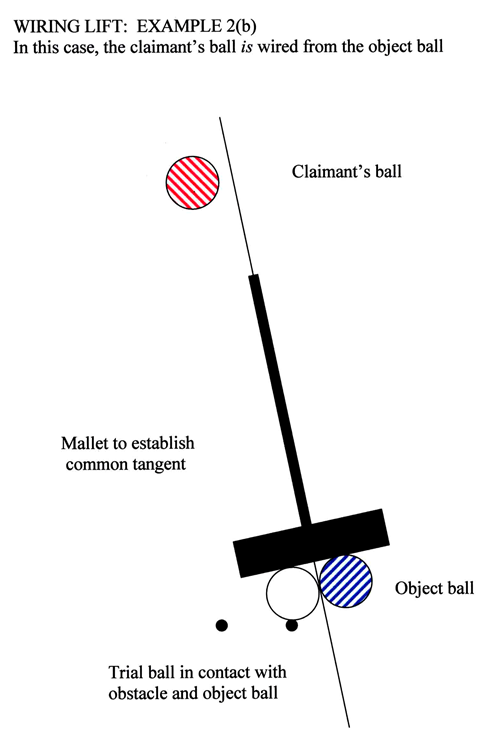

Diagram 2 illustrates a less common - and very deceptive - case where the target is close to (in this example, in front of) the obstruction and a mallet must be used to identify the common tangent which defines the line of the hypothetical stroke. (This relies on the geometrical fact that the common tangent to two touching circles is perpendicular to the line joining their centres). Remember that 'the benefit of any doubt should be given to the claimant' [Reg R3.7].

As with marking balls (see above), the edges of the balls will be a more accurate measure of their alignments than their centres. A practical point to remember is that a single trial ball can be surprisingly deceptive, an unaided ocular test still more so; and remember that a ball is not an obstacle - even if it is itself wired from the claimant's ball - for wiring purposes.

- Impeded swing [Law 16.4]

This is the most difficult claim to test. When it is the backswing which is potentially hampered, the striker should be asked to demonstrate his normal swing (with the mallet he will use for the turn) along the line of the most hampered shot, but translated a foot or so parallel to the line; and you should observe both the back of the backswing (from a point level with the hoop and at right angles to the line, with the eyes at the same height as the crown of the hoop) and the straightness of the swing in relation to the line of aim. Remember that the striker must be able to 'drive [the ball] freely' towards the target [Law 16.4.1]. Even if it is only a matter of inches away, he must be able to take a full swing.

If the problem is the last fraction of an inch for the forward swing (the striker's ball is resting against the hoop, for instance), there is no need to check the swing but you will need to assess whether ball or hoop would be hit first for all possible direct roquets. This is - like a normal wired shot - easier to determine if you place a trial ball against the 'worst' side of the object ball. (See Diagram 3)

- Technical wiring [Law16.3.4]

Do not forget that if any part of the striker's ball is in the jaws of a hoop, the claim is valid (unless it is also in contact with another ball [Law 16.1)] even if - in reality - the striker could roquet any part of the object ball with any fair shot. The jaws include the whole area enclosed by the uprights [Glossary]: the ball does not need to show through on the 'other' side.

Appendix 3.5: Wiring Diagrams

Click on any diagram to see a larger version

Appendix 3.6: Advice to Referees on Double Taps for both AC and GC

(Taken from The Croquet Gazette, April 2008)

Written by Ian Vincent, Chairman, Laws Committee

Edited for the Examining Referee Manual by Barry Keen

1. Introduction

2. The Law

3. Single Ball Strokes

4. Clearance and Scatter Shots

5. Roquets and Rushes (AC only)

6. Croquet Strokes (and Clearance or Scatter Strokes with the Balls in Contact)

1. Introduction

In the February 2008 Gazette, a description of the high-speed photography undertaken at Bowdon was given. Advice from the Laws and Rules Committees about the implications for players and referees was promised. This advice has been written following the recent revisions of both the Association Croquet (AC) and Golf Croquet (GC) Laws, which were undertaken in the light of the findings. It covers strokes in which it is suspected that there may have been more than one contact between the mallet and the ball hit by it (the striker's ball, SB), and hence which might have been faults under Law 29 in AC, or striking faults under Rule 11 in GC.

2. The Law

For AC, the relevant parts of Law 29 are:

"29.1 ACTIONS THAT CONSTITUTE FAULTS Subject to the exemptions and limitations specified in Law 29.2 a fault is committed during the striking period if the striker:

- 29.1.6 allows the mallet:

- 29.1.6.1 to contact the striker's ball more than once in a croquet stroke, or continuation stroke when the striker's ball is touching another ball (for exemptions see Law 29.2.4 and for limitations see Law 29.2.5); or

- 29.1.6.2 to contact the striker's ball more than once in any other stroke (for exemptions see Law 29.2.4); or

- 29.1.6.3 to remain in contact with the striker's ball for an observable period in any stroke (for exemptions see Law 29.2.4 and for limitations see Law 29.2.6);

- 29.1.7 allows the mallet to be in contact with the striker's ball after the striker's ball has hit another ball (for exemptions see Law 29.2.4 and for limitations see Law 29.2.7);

29.2 EXEMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS

- 29.2.4 Contact between the mallet and the striker's ball is not a fault under Laws 29.1.6 or 29.1.7 if it occurs after the striker's ball:

- 29.2.4.1 makes a roquet; or

- 29.2.4.2 scores the peg point; or

- 29.2.4.3 hits a ball pegged out in the stroke.

- 29.2.5 A multiple contact between the mallet and the striker's ball is a fault under Law 29.1.6.1 only if the striker or a referee or other person asked to adjudicate the stroke, aided by nothing more than spectacles or contact lenses, sees a separation between mallet and ball followed by a second contact between them.

- 29.2.6 The mallet remaining in contact with the striker's ball for an observable period is a fault under Law 29.1.6.3 if the prolonged contact is visible or audible to the striker or a referee or other person asked to adjudicate the stroke, aided by nothing more than spectacles, contact lenses or hearing aids.

- 29.2.7 The mallet being in contact with the striker's ball after the striker's ball has hit another ball is a fault under Law 29.1.7 if the continuation of contact is visible or audible to the striker or a referee or other person asked to adjudicate the stroke, aided by nothing more than spectacles, contact lenses or hearing aids, or if it can be deduced from observation of the trajectories and speeds of the balls involved compared to what would occur in a lawful stroke of the same type."

For GC, the relevant parts of Rule 11 are:

"11.1 Subject to Rule 11.3, a fault is committed by a player who, during the striking period:

- 11.2.4 strikes a ball with the mallet more than once in the same stroke or allows a ball to retouch the mallet; or

- 11.2.5 maintains contact between the mallet and a ball; or

- 11.2.6 causes a ball, while still in contact with the mallet, to touch a hoop, the peg or, unless the balls were in contact before the stroke, another ball; or"

Although the wording in the two codes are different (partly due to different revision timetables), the intent is the same, except for the additional complications of roquets and peg-outs in AC.

Note that these provisions only apply during the striking period. Contact between a mallet and a ball outside this period is not penalised, though the ball may have to be replaced under AC Law 36 (and the striker may be prevented from subsequently playing a critical stroke with it), or GC Rule 9.2.

There are other faults that cover touching a ball other than the striker's ball with the mallet, or having the SB in contact with the mallet and a hoop or peg simultaneously (a crush). These are not covered here, except to note that the filming confirmed the view that crushes are unlikely (most potential ones were found to be double taps instead) unless the SB was touching or very close to the upright or peg at the start of the stroke.

The standard of proof required to declare a default is defined, in Law 29.6 for AC, to be that the referee or striker believes it more likely than not that a fault was committed.

3. Single Ball Strokes

These are strokes in which the SB is not touching, and does not subsequently hit, any other ball.

The filming shows that there is only a single contact between the mallet and the SB if the ball is hit with a free swing and there is nothing to prevent the ball escaping from the mallet. The contact time is of the order of 1/1000th of a second, which is not considered to be "an observable period", by either sight or sound, under Law 29.1.6.3. Thus no fault is committed in a normal single ball stroke.

A fault may occur, however, under Laws 29.1.6.2 or GC Rule 11.2.4 in at least four special cases:

- the SB hits a hoop or the peg (unless, in AC, it is pegged out) and bounces back into the path of the mallet. This is a serious risk in close, angled, hoop attempts

- the striker hits steeply down on the ball (e.g. in a hammer stroke or poorly executed jump stroke)

- the striker has a restricted backswing and so has to hold the mallet further down the shaft than normal (thus increasing the effective weight of the head) and force the mallet forward to get sufficient energy into the ball

- the striker deliberately makes the mallet catch up with the ball (perhaps to steer it). Prolonged contact between the ball and the mallet could also be faulted under Laws 29.1.6.3 or GC Rule 11.2.5, but, as with crushes, apparently continuous contact is likely in fact to have been multiple contacts.

However, either way, trying to steer a ball is a fault and a referee can declare it as such, even if not able to state with certainty which sub-law it came under.

4. Clearance and Scatter Shots

These are strokes in which the SB is not touching another ball, but subsequently hits one (to clear or promote it in GC, or to scatter it in AC).

If the balls are more than a centimetre or so apart and hit flat along the line of centres, a double tap will occur unless the mallet is stopped before it catches up with the SB. This would be a fault under AC Law 29.1.6.2 or GC Rule 11.2.4 (like in case 3(a) above). On the other hand, if the balls are very close, say a few millimetres apart, then the mallet will still be in contact with the SB when the SB hits the other ball. However, there is no escape for the striker, as this is caught by AC Law 29.1.7 or GC Rule 11.2.6. Again, a referee does not need to decide which sub-law applies, provided that he is satisfied that one or other does.

In the case where the SB is being hit straight at the other ball, it is very easy to tell if a fault has been committed. It will have been a clean stroke if the SB stops after hitting the other ball. Conversely, if it carries on more than for more than an eighth of the distance that the other ball went then the strike will have been a fault, even if it sounds clean, unless it is clear that the SB jumped partly or cleanly over the other ball. The reasoning is that more energy must have been imparted to the SB after it hit the other one and this can only have come from the mallet.

Things are less clear-cut if the balls move apart at an angle, but as a rule of thumb the stroke will be a fault if they move apart at much less than a right-angle.

5. Roquets and Rushes (AC Only)

This section covers the case when the SB makes a roquet. A stroke that would be a fault if the ball that the SB hit was dead (see 4 above) is exempted from being a fault, by Laws 29.2.4.1, if the ball was live. The reason for this is that it would otherwise be impossible to lawfully roquet a ball that was very close to the SB. Note, however, that the exemption only applies if the potential fault occurred after the SB made the roquet, not if it results from an attempt to get the SB to reach the ball in a hampered stroke.

However, there are two special cases to consider:

- In the case of hoop and roquet (Law 21.2), the striker gets the benefit of the exemption provided that the SB ends up having run the hoop, even if it would not have done if the mallet had not hit it again. (However, see (b) if the SB also touches an upright).

- The exemption does not apply (and thus a fault committed) if, between the roquet and being hit again by the mallet, the SB touches the peg, a hoop upright, or a third ball. This can apply in angled hoop and roquet positions, or if the striker is trying to promote a third ball into court when playing a rush (after a previous gentle cannon). To complete the story, the exemption does apply if the SB hits a hoop, then makes a roquet, and only then does the mallet catch up with it.

6. Croquet Strokes (and Clearance or Scatter Strokes with the Balls in Contact)

Although the original article said that no particular problems were shown by the filming of croquet strokes, it should be noted that contact times were many times greater than for single ball strokes and that there was at least a suspicion of multiple contacts in the half-rolls, even though they would be regarded as perfectly acceptable. It is for this reason that the fault is limited to contacts that could be observed with the unaided eye by Law 29.2.5 and "observable" is included in Law 29.1.6.3. The intention is to exclude multiple taps that could only be detected by photography, not the human eye, from being faulted, to ensure that the game as we know it can lawfully be played. Another reason for doing so is that the striker generally gains no advantage (in terms of where the balls end up) by playing a dirty rather than a cleanly executed stroke.

Thus few, if any, ordinary croquet strokes would be expected to be faulted for double taps or maintenance of contact, and the same applies to scatter strokes or, in GC, strokes in which SB starts in contact with another ball. However, it is still a fault to blatantly shepherd the SB in a hoop approach, or to play an extreme pass roll in which the mallet has clearly hit the SB a second time. See also sections 4 and 5 above if the SB hits another ball in the stroke (a cannon).

Contents...

Contents...

Using this website

Using this website